Classic Blog

The Switch

By Brenda Rogers

In a meeting with: a public school principal, school psychologist, school nurse, general education teacher, special education teacher, school system attorney, mother of a student and a special education advocate, decisions are made about whether or not a disabled student is entitled to support in school. In this meeting, the law says everyone at the table is an equal member of one team. The reality is that mom and her advocate are not equal members of the team; mom and her advocate have no authority but mom holds the powers of: veto, appealing to higher authority in cases of school district procedural lawlessness and requesting a due process hearing before a tribunal judge, if the school will not appropriately educate her child.

The team’s purpose is to help a struggling student succeed in school. The student’s team comes together to examine evidence that determines if the student is eligible for an Independent Education Plan (IEP). If the student gets the IEP, the student will have government protections as a disabled person. These government protections allow the student to get specially designed instruction, accommodations, modifications and supportive services that ensure meaningful annual progress in school. Without these protections, the student is free to fall further and further behind each passing year, without any special help. The following story is based on real life events but names and cities have been removed to protect the innocent.

In a California meeting, a school psychologist presents information to the student’s team. The school psychologist reminds the team that this meeting is part 2 of a meeting to decide if a student is eligible for special education. The psychologist reminds the team that the student has a medically diagnosed learning disability and academic achievement testing shows a couple lower scores in reading but not enough to be considered alarming. Next, the school psychologist presents the team with a report of student grades. “The student is passing in all curricular areas at or above grade level,” says the school psychologist. Puzzled by the report of grades passed around to all team members, the advocate asks the psychologist: “did you notice that the grades show one curriculum area where the student is not passing?”

The teacher answers: “the low trimester grade reflects the fact that the student just hasn’t been taught 100 percent of the information for the school year in that area of the curriculum.” Confused by the answer, the advocate replies: “can you tell me what criteria you used to produce the grade?” “this grade reflects student test performance in this one area. The student’s tests are below passing level,” says the teacher. Probing for clarification, the advocate says: “that means that the student was taught the curriculum in that area and then tested.” The meeting room goes quiet again. The educators sit silently stern faced looking at mom and her advocate, as if to show their forced tolerance of an impolite interruption of their meeting. With a Cheshire grin, the advocate breaks the silence by asking the school psychologist: “is it standard practice to test students on curriculum not yet taught?” After a brief silent pause, the advocate inquisitively asks: “If the student is passing at or above grade level in all curricular areas, why do we see these consistently failing grades in language arts?” With a monotone voice, the school psychologist solemnly replies: “There is one area where the student is not passing at grade level.”

Mom then adds: “just to get the work done in class, my child says she has to get extra help in Language Arts from you every day.” In response, the teacher defensively replies: “the student can do the work. I’ve seen her do the work. The student just doesn’t want to because she is too busy writing notes to her friends in class.” Mom responds by saying: “I thought the notes stopped at the beginning of the year, when my child was seated off by herself five feet away from all the other students in language arts class.” Irritated, the teacher huffs: “she still wants to write notes even if she can’t send them. She can do the work. I know. I’m in that class and I have seen your child do it.”

Quickly, with an air of authority, the principal interjects: “the student does not need an IEP because the student’s disability is not impacting academic achievement.” Following the principal’s lead, the attorney gives what appears to be the final word and concludes by saying: “The school team agrees that the student is passing in all curricular areas. The student is not entitled to an IEP.” Taking an unexpected final show of authority, the principal looks at mom and her advocate and states: “This meeting is over,” before she orders the school nurse to make several copies of the official paperwork.

The meeting is officially over. The school nurse walks out the door to make copies in another room. Mom and her advocate sit waiting like strangers, in a schoolroom, with educators who look quite at home in their environment. Within 30 seconds of meetings end, school employees start chatting. Lower status educators begin to giggle when the school principal fills the quiet noise with a personal memory to illustrate her experience and age. “I was in college when personal computers were first made available to the public. Now, we create official documents on notebook computers,” says the principal. The school’s attorney chimes in recounting how old and where she was the first time she connected to the internet, using dial up service. The psychologist then offered her short story before the group, with a melodious tone, began light heartedly chit chatting about various topics.

Meanwhile, mom and her advocate sit frozen and speechless, with wide eyes, looking down at the data sitting on the table showing the student has been failing language arts all year, apparently with extra help from the teacher. Mom and her advocate sit at the table, with educators who are now completely in their own world. For the educators, and their attorney, the mother and her advocate are as invisible as loitering homeless at a gas station. A passerby peeking in the room, at that moment, would think these educators, and their attorney, are having a tea party.

Mom and her advocate sit solemnly speechless at a boisterous table gobsmacked by the switch. Mom and her advocate just witnessed school employees switch realities from being in an official government agency meeting to being part of a social club within 30 seconds. The reality switch occurred so smoothly and quickly that it looked like a habit, as well rehearsed as a woman washing her hands after using a public bathroom.

The reality switch happened right after the advocate and mom watched these government bureaucrats switch the analytic criteria used to make a judgment about eligibility requirements for government protections. The valid criteria used to determine eligibility comes from evidence showing student grades in all curricular areas are passing. For these educators, in this meeting, the criteria for passing at grade level in all curricular areas is based on grades showing failure in one curricular area (known for its relationship to the student’s medically diagnosed disability).

After mom and her advocate passed through the looking glass, they were shocked and disoriented by this new reality grounded in strange physics and foreign customs. If the criteria used by these educators to determine passing in all curricular areas is valid, then all students with D’s and F’s, in all public school classes, are now passing. Impromptu analytics notwithstanding, this student’s ability to access her rightful government protections, as a disabled student, has been denied based on changing eligibility criteria determined by this group of bureaucrats, now rhythmically chatting to the tune of Mad Hatter’s Very Merry Unbirthday.

Still stunned by hearing the equivalent of Wonderland’s Queen say: “off with her head,” mom and her advocate start watching the door for the way back through the mirror. Mom and her advocate are in no mood to celebrate mundane free time enjoyed by government bureaucrats. Mom and her advocate are not amused by the slight of hand and slip of wrist decision-making process just passed off as law and order. The student just fell through the cracks in the education system. Mom and her advocate just witnessed the truth. The student’s teachers, the administration, and their attorney, pushed the student through the cracks because they all know their actions have no accountability in a world where working poor mothers and fathers cannot afford to purchase equality under the law.

Finally, the nurse walks back into the room. The government bureaucrats quiet down. Mom and her advocate sigh in relief knowing that the heaviness of the discomfort is over. The documents stating the child cannot have an IEP are handed to mom and her advocate before the pair exits the room.

In the parking lot, mom tells her advocate: “I can’t believe what just happened. The educators just did whatever they wanted to do. They don’t care about my child at all. I guess all I can do is wait and try again next year because we can’t afford an attorney. Attorneys want thousands of dollars in retainers or monthly payments. We cannot afford either option. It seems like my child has to fall further behind, like maybe three or four years below grade level, before I can get any help from the school.”

The advocate replies: “It comes down to a few desperate options: we can wait for your child to fall further behind and try again, we can file a uniform complaint on the school psychologist for not accounting for the failing grade in one curricular area and hope this forces the team to meet again and reconsider the grades, or you can take the school system to due process yourself. I know you don’t want to wait for deeper failure. I also know you have no college education, no experience and are not prepared to present your case to a judge. So, would you like to file a uniform complaint on an employee?”

Mom looks like she’s been punched in the chest. Mom asks: “So, we have to come against someone’s job or be our own lawyer? These people work with my child. If I file a complaint on someone that impacts their job, how will they treat my child? what does the state expect us to do when we have no money for lawyers?”

The advocate explains: “well, it comes down to rights versus relationships. Your child has failed all year. We can’t get your child help to pass and we know she has a disability. You risk the relationship disruption to keep from walking blindly in the dark, as your own attorney. The thing about retaliation is that school employees are less likely to retaliate knowing you are able to file complaints against them for dereliction of duty on the job.”

With a sigh of hesitation, mom says: “let’s file the complaint.” The advocate console’s mom by explaining how they were backed into this corner. Mom’s advocate explains: “I’m sorry. The problem here involves the substance of decision making, rather than observations of procedural lawlessness. If the school would have failed to perform an action required by law, we could use state Procedural Safeguards to force lawful treatment. And, if this type of problem would have happened before September of 2017, I could have taken this case to due process for you, without charging. You know, advocates used to be able to represent parents in due process hearings. I could have at least prepared the case and given you a fighting chance in front of an administrative law judge. But, the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH), the agency performing due process hearings and mediations for schools, called the California BAR association asking for clarification about advocates in due process. OAH asked the BAR to decide if it is legal for California advocates to represent parents in due process hearings. You know, OAH did not tell the BAR association that advocates have been representing parents in due process since the 1980’s and non-attorney school employees, in some California school districts, represent schools. Without knowing the history of due process in CA, the BAR association wrote a letter stating that it is unlawful for advocates to represent parents in due process hearings.”

The advocate adds: “Do you know what makes this situation even worse? If your child commits a crime, your child can have a free public defender. The state will pay an attorney to ensure your child gets due process of law in cases of criminal behavior. But, in cases where your lawfully behaving child’s future life chances at stake, the state just decided that you low-income parents are on your own to ensure your child gets due process of law.”

In this case, the advocate helped mom by appealing to a higher authority within the bureaucracy itself. Since the advocate could not use the state due to the problem residing in decision making criteria, the advocate was forced to use the bureaucracy’s accountability system for job performance. Mom’s uniform complaint against the school psychologist helped because the school psychologist’s performance was under evaluation by her superiors in the school district.

The team met again and was forced to consider the failing grades in language arts. Interestingly, the whole team agreed the student qualified for an IEP under the category of specific learning disability due to the evidence of persistent failing grades in language arts, the diagnosis of a learning disability and a rather significant gap between academic achievement in reading comprehension and phonemic awareness and her full scale IQ score. Previously, the team had overlooked the gap between low academic achievement scores and overall IQ score because the difference was between 15 and 19 points. The California educators insisted that 21 points was needed to consider the student learning disabled. The entire process of getting an IEP took over 10 months and spanned two academic years, because of summer break.

The student received remediation in phonemic awareness skills and her reading comprehension improved. The student was behind in language arts by three grade levels before the student’s grades began to improve. By the end of high school, the student was able to graduate with a diploma.

By the time this student secured an IEP, the student was far below grade level in an area that could impact her future. While the student did get some reading remediation service, it was minimal and took an entire school year to make a difference. There was no way to get a quantity of intervention sufficient to help the student quickly recover skills because there was no compensatory education services for the time lost by educator dereliction of duty.

Ironically, there is no guarantee the student would have won her due process case. There was a high probability that the school district would have settled the case because the student continued to fail in language arts as time passed. Had this case gone to due process, the student may have had a chance to get compensatory services that would have brought her reading skills up to grade level much sooner than the way things occurred without due process. In the end, advocacy helped but getting help was much slower without the option of a due process hearing.

This is a cautionary tale. Not all IEP teams operate as if the meeting takes place in a state of altered reality. Nevertheless, many parents and advocates walk through the looking glass when they enter the IEP meeting. In many states, advocates are able to represent parents in due process hearings. Because the method of advocacy used in this case does not seek justice for a student, compensatory services were not an option. Appealing to a higher authority within the school district itself helped stop the use of some strange analytic criteria used in decision making and helped get a needed IEP for the student. However, appealing to a higher authority within the district does not stop IEP meetings from becoming soul battering experiences in wonderland.

© Brenda Rogers, 2017

The Special Day Class

The special day class (SDC) is a public school classroom designed for special needs students. School districts often stratify SDCs by level of functional performance. In other words, SDC are often ranked from mild to moderate to severe. Mild classes teach students with mild impairments such as mild autism, high functioning intellectual disability, and average students with severe behavior problems. Moderate and severe SDCs educate students with more severe disabling conditions.

We had a case in which a student with a low average IQ (84) was placed in an 1st grade SDC class because she was a slower learner who could not keep up with the pace of learning in the mainstream classroom. When the student was placed in the SDC, her IQ was 84 and her reading achievement scores were also found to cluster around a standard score of 80. We got the case when the student was entering 4th grade. In 4th grade, the student’s triennial assessment revealed her IQ had dropped to 71 and her reading achievement scores were below the standard score of 70.

The science of measuring IQ teaches us that a person’s IQ is fairly consistent over time. If a person’s IQ is measured at 135 in 1st grade, we should expect that person to have between a 130 and 140 IQ three years late (anticipating small variances over time due to error and insignificant change due to daily changes in attention, mood or haivng a caugh or cold while being tested). However, when we see drops in IQ and achievement over 10 points, this drop is explained by either error or something called the Matthew Effect.

The Matthew Effect explains how young children who are poor readers become increasingly unable to benefit from education as they age. If young poor readers do not get appropriate early intervention, these students loose out on learning background knowledge and understanding how print is organized to convey information (http://www.wrightslaw.com/info/test.matthew.effect.htm). As a result, the poor reader falls further and further behind their peers in their basic understanding of the world around them. Meanwhile, the gap between the poor reader and the average student gets wider and wider. When measuring the IQ of poor readers that do not receive appropriate reading remediation, we may see significant drops in IQ scores as these students age.

The comparison of 1st and 4th grade data for our student revealed that the SDC placement was literally cognitively impairing the student. In other words, the SDC placement was not appropriate and the techniques used to educate the child were not helping the child learn to read or access the curriculum. In order to help this child, we got the child an Independent Educational Evaluation to accurately determine the student’s needs.

In reality, the child’s needs were not met in the SDC placement and the school had not addressed the severe auditory processing deficits this child suffered from. An appropriate placement for this child needed to address her unique needs related to auditory processing in order to help this child learn to read and access the school curriculum. Simply placing the student in an SDC class for slower learners did not address her unique needs and did not help educate this child.

Does the primary qualifying category on the IEP matter?

The category for qualification in special education is important. For example, if your child has been diagnosed with Autism but the qualifying category for enrollment in special education is Emotional Disturbance, the program designed for your child will focus upon the needs of a student with Emotional Disturbances and not Autism. Therefore, it is important for your child’s qualifying category within special education to match the actual diagnosis your child has received from a medical doctor or professional child psychologist with a doctorate in medical psychiatry or educational psychology.

The schools are not equipped with medical doctors and are not in a position to diagnose students. The school psychologist is in a position to screen students for manifestations of childhood disorders. The school psychologist is not qualified to diagnose childhood disorders. It is important that a school psychologist’s data reflect the diagnosis of medical doctors and qualified psychology experts. If the school psychologist is not willing to acknowledge the relationship between his/her data and the diagnosis of qualified practitioners, parents need to do their homework about the IEP process and seek assistance from an advocate. It is important that the student’s qualifying category for special education reflect the childhood disorder causing the need for special education and related services.

Does school policy violate LRE?

A mom enrolled her daughter in the 9th grade, as a student with special needs. The school counselor told mom her teenager must give up her only elective to take a “study-skills” class because all IEP students must take this “study-skills” class during their freshman, softmore, and junior years. Mom questioned the fairness of this policy because it takes away her daughter’s only elective. Both the counselor and the IEP team insisted that district policy requires all students with IEPs to take a “study-skills” class and the only way to take this class is to forfeit the elective.

Students without IEPs get to take electives and do not have to take the study-skills class. So, mom called an advocate. When mom attended the IEP meeting with the advocate, the IEP team agreed with the advocate that the student’s unique needs were not met by the study-skills class because the student had no history of problems with work completion, study-skills or homework completion. When the advocate questioned the IEP team about district policy requiring only IEP students to take the study-skills class, the IEP team explained that they like IEP students to take this class but it is not absolutely required for all students. The student’s schedule now includes an elective and no study-skills course.

In this case, the school policy selecting only students with IEPs to take a special class that all other students are not required to take violates the law.

“Each public agency must ensure that –

- (i) To the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are nondisabled; and

- (ii) Special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only if the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.”

- (ii) Special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only if the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.”

- (ii) Special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only if the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.”

Any school that requires all students with an IEP to attend a special class non-disabled peers are not required to take violates Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) law. Just because school officials say: “this is our school policy,” does not make the school policy legal. An illegal school policy can be challenged.

Contact your state procedural safeguards hotline to file a state complaint for your child or a variance for all special education students in your school!

Lawlessness

I am disturbed by procedural lawlessness. For instance, a California school district decided to ignore a written assessment request. Seven months after mom requested her child be assessed for reading problems, the child was assessed. Then, an assessment was conducted without a valid consent form signed by a parent. As an advocate, the “do what you want” standard operating procedure is a problem for the general public. The public school is a core government agency. When core government agencies do not consider procedural law important in performing core government functions, it’s the community that has a lawless government agency.

Law and order in society is important. Procedural law in special education exists so that disabled students can expect to have their needs met within a time frame recognizing developmental needs of aging children. When assessment and intervention are delayed for long periods of time, a child experiences educational loss in a fast paced system. Not complying with legal time limits means that disabled students fall further and further behind while the curriculum advances farther and farther ahead.

In the long run, ignoring timelines creates loss of educational benefit. Students with reading disorders, for example, may have their reading problems ignored for several years before receiving any intervention. Some people leave high school unable to read and some people leave high school with very low reading skills. In cases where students leave school unprepared for even entry level employment, it’s often the school giving the community young adults that are ill prepared for independence.

The school and the school district must be held accountable for procedural compliance with law in identifying students with special needs and in delivering special education. As community members, don’t we have a right to demand our public institutions comply with procedural law? Our kids need us to demand schools comply with law.

The Need for Public Oversight

The IEP is a wonderful document. I’m truly grateful to those wonderful people that created the Education for All Handicapped Act. There was a time when disabled children were not allowed to go to school. Before the 1979 EHA, students with disabilities were sent home from school or not allowed to attend at all. The EHA, and its successor Individuals with Disabilities Education Act IDEA, are truly wonderful laws. These laws afford disabled children the right to be in school and the right to fair treatment.

Having rights for disabled students in public schools does not mean that these rights are followed by school personnel. In some cases, school employees do not know about special education laws and in other cases, school personnel work alone and/or together to ensure a very narrow version of IDEA operates in the school. Because schools differ greatly in their implementation of IDEA, it is critically important that parents know what their child’s rights are and how to use these rights to ensure fair and legal treatment.

Unfortunately, special education does not enjoy the same public scrutiny that the prison system enjoys. Within the corrections system, individuals, attorneys, and watchdog organizations combine to keep state power in check by creating systems of public oversight. Special education operates with less accountability than the prison system. Most of what happens to prisoners occurs in private but inmates are old enough to file complaints about illegal and inhumane treatment. Children, especially disabled children, are often ill-equipped to complain or don’t know that their experience is not legal.

Knowledge is power. While the IEP is a private document, and the systematic procedural violations of law committed by schools systems are done in private, the more children and parents know their rights, the more violation of procedural law can be exposed. When parents discover procedures were violated in the administration of their child’s education, the typical response is to either to pretend these violations didn’t happen or call someone for help. Little, if any, lawlessness is reported to state agencies through complaints to the state procedural safeguards unit at the State Department of Education. For example, during the 2014-2015 school year, there were 4991 state procedural compliance complaints filed in the United States while almost 200,000 due process cases were filed (Cadreworks.org). Since 90 percent of due process cases end in private settlements, the written state complaint is the only way to track procedural violations in public schools.

The lack of public accountability for procedural lawlessness is unacceptable. Children with disabilities should be identified as young as possible and schools must be held accountable for lawful treatment of students with special needs. Children with special needs deserve as much accountability as someone in the prison system. Procedural compliance with law in special education needs to be an important public issue. There has to be a way to get public oversight in school procedural practices. We need IEP police.

The IEP Police

Parent advocacy is important. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) makes the parent the child’s advocate. The parent is the advocate because law makers know that school systems base their decisions about a child’s needs based upon how much money is in the school budget. In the first section of the IDEA law, the text states that In IEP meetings, parents are primarily concerned with the outcome of their child’s education and school district personnel are primarily concerned with the school’s budget. The law recognizes that IEP meetings are locations where people with competing interests are expected to work together and come to agreement about an appropriate education plan. However, the law also states that the parent is the only one in the IEP meeting expected to protect the child’s interests.

Parents need to make sure they read their rights. Parents also need to know what rules the school has to follow in administering special education. Almost every time I have reviewed a case since 1999, the school has violated procedural law in several areas of administration of special education. In fact, the failure to administer procedurally lawful special education is the cause of most conflict I confront as an advocate. Therefore, I am blogging about procedural law in special education as a first step in creating IEP Police to function as a watch dog organization for public schools.

What to do when schools violate procedural laws

File a State Compliance Complaint

The law requires that all students with IEPs receive a triennial assessment every three years. Triennial assessments are also good practice to ensure a student has current psychoeducational data in order to develop a meaningful IEP. I recently consulted on a case in which a high school student, with Downs Syndrome, had an IEP created using a triennial assessment completed in elementary school. In this case, the student’s goals had not changed in 5 years. The fact that the district never changed the goals made sense because the district never collected any data on progress. When no new assessments are conducted and progress is not tracked, the IEP team has no data to use in making new goals. In this case, the parent brought an advocate to act as IEP Police and ensure the school comply with procedural law.

When the school does not comply with procedural law in California, parents can file a state procedural compliance complaint. Parents have the right to file this complaint and get the California Department of Education to force the school to follow procedural law. In cases where procedures were not followed and the child’s IEP was not implemented, the department of education can correct the situation. For example, if the child was denied speech and language therapy for most of the school year but should have received speech services 3x per week for 30 minutes each session, these sessions need to be made up. The child has the right to those missed sessions and all pending sessions. The department of education has the ability to make the school implement the IEP and provide compensatory services. Please file a state procedural compliance complaint when the school does not follow the law.

Do You Need An Advocate?

I think that advocates are critically necessary in an institutional society. Would you try to sew a garment if you did not know how to stitch by hand or use a sewing machine? How can parents effectively advocate for their children without having expertise in special education law and the science of assessment? Parents need access to experts that can help them understand the special education process. I believe parents that face difficult circumstances surrounding their child’s education need access to advocates for guidance, information and advice. Parents that have access to the information, advice and guidance of an advocate are better equipped to make informed decisions for their children.

Rights v. Relationships

While conducting research about special education, I came across common themes in parent experiences trying to get help for their children. Most parents I spoke with have a strong sense that something about their child’s education needs to change. These parents witness their child either falling behind academically or struggling socially and/or behaviorally. However, these same parents either think they have no options and take no action or are aimlessly searching for someone other than the school to tell them how to help their child.

Part of the problem includes most parents not knowing what their child’s disability is. Lack of knowledge about the disability explains the confusion I see on parent’s faces when I ask: “what is your child’s specific disability?” I see the most confusion in the area of learning disabilities. Many people respond to my question by stating: “I’m not exactly sure” or “We think it is but…..” Many parents can describe their child’s difficulties in school but do not know what causes the problems. As a result of not knowing what type of underlying disability their child is struggling with, most parents do not know what an appropriate education for their child should look like.

I see fear as a key factor keeping parents from utilizing the school as a resource in getting help. I often hear parents confess that they have thought about asking the school for help but fear what the teacher might think about them if they ask for something extra or fear the amount of resistance they predict facing when presenting their request to an actual IEP team. Many people fear asking for needed help will disrupt relationships with teachers and office staff at the school. Parents also report fearing that their child will be treated badly if they ask for extra help or services.

Most parents report that the school has never offered any information about what is available to their child and therefore do not know what to ask for. Some parents admit that they would like their child to receive extra help with basic academic skills like reading, writing, and arithmetic but did not know the school had a responsibility to help their special education child outside of the classroom.

I like to tell parents that they need to think about their child’s education in terms of priorities. There are two priorities parents face in the education process. First, the priority to parent the child requires oversight of education and support in getting the child to succeed in school. Second, the priority of maintaining relationships with teachers and staff require parents to communicate and cooperate with school personnel. These two priorities usually work together in the educational process. However, when a parent of a special education student witnesses their child falling behind or failing in school, these two priorities my begin to conflict. Often parents have to choose between their relationships and their child’s needs. In special education, the choice is often between rights and relationships.

The child has a right to whatever programs and services are necessary to accommodate the disability in such a way that the child can succeed in school. The law requires that the parent become the child advocate. The law places the parent, in the role as advocate, in a precarious situation. Parents often have to choose between the priority of maintaining status quo relationships and the priority of advocacy for the child. Maintaining relationships and advocating for your child does not have to be an either / or situation.

There is always the potential for problems with relationships when making requests for services during an IEP team meeting. However, the child is the ultimate recipient of the repercussions. Parental action can produce immediate results in terms of intervention services and student improvement. Parent action can possibly disrupt relationships. Parent inaction will produce consequences for the child over time. No response to falling or failing grades will eventually result in a reduced ability to benefit from education and eventual school failure. In the case of action or inaction, there will be repercussions for the child. In other words, even no action produces reaction.

Advocates and attorneys are helpful because they allow the parent to separate the advocacy role from the parental role. The parent can fill the advocacy role with an advocate while focusing on their parental priority to maintain relationships with the school. Of course, using advocates does not preclude a parent from relationship problems but it does often help take the focus off of the parent’s actions. Research shows that attorneys have a serious impact upon both the IEP process and the parent / school relationship. In my experience, schools prefer to work with advocates if given the choice between advocates and attorneys. However, sometimes an attorney is absolutely necessary because the school persists in both procedural and substantive lawlessness. In the cases where the school will not give a child an appropriate education, even with an advocate’s assistance, attorneys must be recruited.

© BrendaRogers 2006

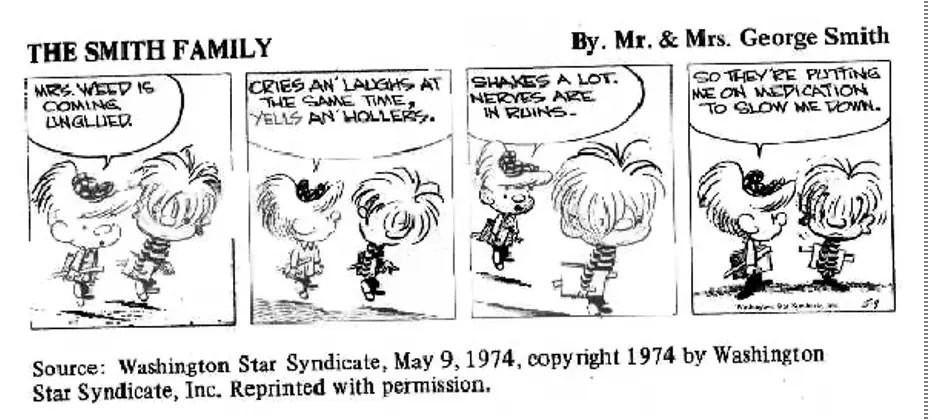

Some Humor

The cartoon represents one perspective on the use of psycho-stimulant medication in children diagnosed with a disability. For parents facing a situation like the one represented in this cartoon, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act makes it illegal to deny a child an education because parents will not give the child psychostimulant medication. Some parents are against medication and others consider medication an important part of treatment. At ACE, we respect the freedom of each parent to form their own opinion about the use of psychostimulant medications.

One Path To Low Wage Labor

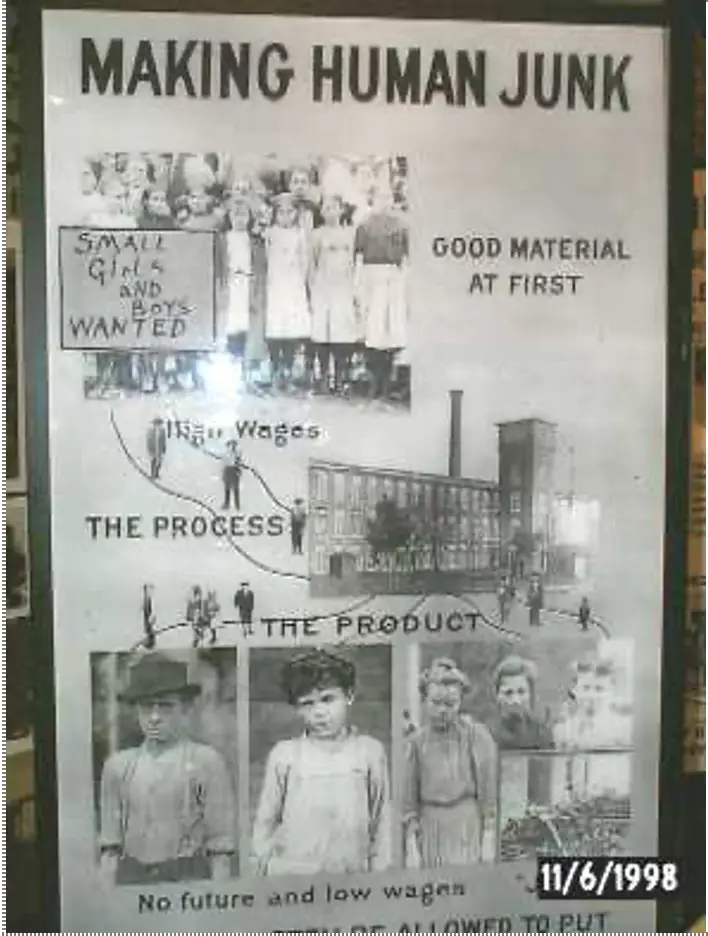

One Path to Low Wage Labor

The poster is from the Women’s Movement of the 1920’s and was displayed at the Washington DC Smithsonian Historical Museum. This poster, about child labor, makes me think about the human product of modern American public schools. In some cases, the product of an American public school education is the destruction of a person’s self-image and the ruin of personal potential.

Systematic lawless administration of special education is the number one problem for students with IEPs and students needing special education intervention. If the school system would follow procedural law, then over half the conflicts in special education would not exist. For example, I have a case where a student is in 3rd grade but reads at a 1st grade level. I was called because the child was over a year below grade level in reading. The student’s mother explained that she had asked for a special education assessment early in 1st grade but nothing was done. Then, mom asked for a special education assessment early in second grade, by writing a letter, but nothing was done. I advised mom to write another letter requesting assessment and take the letter to the special education department at the distract office. Then, I advised mom to get that letter date stamped received by the district office.

The next thing that happened was that the mother got an assessment plan and the student was assessed. The student qualified for special education as learning disabled. By the time we got the child reading intervention, the child was two years below grade level in reading.

This gap between reading ability and grade level is a serious problem for this student. This student is learning about who he is, as a person, from the experience of sitting in a third grade classroom unable to read what every other kid in that class is reading. In fact, this student cannot even read the tests and quizzes handed out in class. The student failed his quizzes and tests because he can’t read them.

Without requests and advocacy, the child was left sitting at his desk without help and the student is blamed for all failure. We had to attend an IEP meeting to request the accommodation that an aid or RSP teacher read all quizzes and tests, to the student, because the student cannot read. What does the experience of being the only non-reader in 3rd grade teach this child about himself?

This situation could have been prevented. Had the school assessed when the mother first requested (as required by law), the student would not be two years behind. This child’s failure in 3rd grade is caused by the school’s lawlessness of refusing to assess a child when the parent makes the referral for special needs assessment. The school violated child find procedural law.

The worst thing about this situation is that this child is not alone. This same situation is happening to children in every district within every state across the country. Systemic school failure is a group experience caused by school personnel systematic non compliance with procedural law.

So, I ask: “Can lawless administration of special education produce the same ‘human junk’ represented in this poster below?” There is a popular saying in New Orleans that claims: “prison’s estimate their future population density based upon the rate of non-reading boys in 4th grade.” Katie Sanders reports that “…the Nevada Department of Corrections…” revealed that California uses the number of non-readers in 3rd grade to estimates prison populations (http://www.politifact.com/florida/statements/2013/jul/16/kathleen-ford/kathleen-ford-says-private-prisons-use-third-grade/). How much different is product of the compulsory education system for learning disabled special education students of 2018 than the product of the factory labor system for poor children in the 1930’s?

Many learning disabled students enter school as good human material. These students enter school feeling good about themselves. These students want to please their teachers. Then, the process of schooling teaches these students that they are failures and bad students. Children learn to see themselves as bad people. Often children come home and tell their parents “I’m stupid and no-one likes me.” The school experience starts the process of learned self-hatred and if this process is left unchecked, the school produces barely literate adults who believe their personal failure is their own fault. Through the process of systemic lawlessness, the American school system takes advantage of the weaker students within the system and produces an underclass of docile young adults prepared only for a future of low-wage labor.

Blog Content Copyright © 2018 Brenda Rogers M.A./A.B.D.