Our Humble Beginning

The Fight for an Appropriate Education

I was a young single mother struggling to make ends meet while completing college. While a full-time student at the University of California, Irvine, we lived on campus in a family housing track. My son attended the local elementary school.

I tried to facilitate a smooth school experience for my son. Before kindergarten began, I met with the elementary school principal to inform her my son had been diagnosed with ADHD and request an appropriate classroom placement. This meeting only put a target on my son’s back. It didn’t take long before my son’s hyperactivity became difficult to manage and the principal started sending him home early.

As a result of childhood hyperactivity, misguided school personnel reported me to Child Protective Services for bad parenting causing the school behaviors. During my son’s kindergarten school year, I was investigated for child abuse on three separate occasions. All allegations were found to be totally unfounded. In fact, the social workers found that I was enrolled in parenting classes through my church and was a self-disciplined child-centered mother implementing a systematic behavior modification parenting program while both working part-time and managing to maintain a very high college GPA.

Meanwhile, my 5yo son was suffering at school. The learning environment was overstimulating and causing him to try and escape the school experience. My son was running off campus on a daily and weekly basis. The elopements were never followed up by the required incident reports nor was any special education evaluation recommended by school personnel. Rather than follow procedural laws, the principal suspended my son for bad behavior daily and sometimes weekly.

These suspensions and informal send-homes were serious experiences. I was ritually called into the Principal’s office where I found my five year old son waiting for me. I would walk into the office and sit down next to my son, as if we were two children brought to the office for correction. The Principal would close the office door, turn around and sternly tell my son: “you are a bad boy; what you did was wrong; you are suspended.” Then, my five year old would fall into my arms in a fetal position crying. I had to stand up, with my son in my arms, and carry him off school grounds crying because the Principal suspended him. This devastating experience happened often.

Tolerance for behavior problems were unevenly distributed. For example my son was injured, by another student, in the kindergarten classroom and sent to child care with his lip hanging open. My son’s lip needed over 20 stitches. The injury occurred at 10am and the child care providers called me to come get him for medical care at 4pm. Meanwhile, the girl who pushed my son’s face into a table was not suspended, reprimanded nor approached for bad behavior and no incident report report was filed. My son had a scar and bump on his lip for the following 10years.

Suspensions and informal send-homes continued through first grade before social isolation was added to the repertoire. In response to playground hyperactivity, the principal established a system to separate my son from other children. During recess and lunch, the principal made my son spend all time outside the classroom away from other children, with the supervision of a very nice resource teacher. I was told lack of supervisory staff justified exclusion from the playground and peers.

Segregation, shaming, and suspensions began to deeply wound my son’s heart and damage his self-image. My son began hiding under his desk instead of participating in class. After my continued refusal to obey the teacher and give my son Ritalin, the school finally evaluated my son for special education. My son was identified as learning disabled and hyperactive, with an above average IQ.

I was pressured into placing my son in a class with mildly intellectually delayed and autistic students. I was told the autistic classroom was in a school with staff that could supervise my son on the playground and if I agree to the autistic class, my son could play with other children again. By March of first grade, my highly intelligent hyperactive child was placed in classes with moderate to low-functioning Autistic children and wasn’t allowed to learn with his peers.

As a weekly parent volunteer, I saw major problems with the classroom placement. In the Autistic class, my son was not allowed to learn because the other children could not keep up with his ability to explain the words and meaningfully engage in the curriculum. I watched the SDC teacher tell my son “you can’t explain the word that much because the other student’s can’t keep up with you.” I saw this happen weekly but did not demand change because the school “experts” told me this class meets my child’s needs.

By third grade, I determined that my son’s intellectual needs were important and demanded placement change back into the main stream classroom. I argued that my son needs a “mainstream” classroom because the autistic student education was not appropriate for a boy with a very high IQ. The school moved my son back to mainstream third grade.

After a year and a half of warehousing, my son was unprepared for his grade level. By November of third grade, my son would come home every day and say: “I hate myself,” “I’m an idiot,” and “everybody hates me.” I was devastated witnessing my happy, smart son turn into a self-hating, mean and depressed little boy who was systematically denied the opportunity to learn to read, to play with other children and to develop a positive self-image.

Moving my son from warehousing to a mainstream third grade classroom turned out to be a new form soul crushing lessons in self-hatred. The classroom was a visual experience in social stratification (ranking children from best to worst). Children’s work posted on the walls was visually displayed by achievement levels from highest scores, receiving the top spots on the wall, to lowest scores receiving placement at the bottom of each display area. The visual message from the classroom walls was that good students are at the top and bad students are at the bottom. Every week I left volunteering in that third grade classroom, I cried driving home. I personally fell apart while simultaneously pulling myself together to immediately return to work as a university teaching assistant and doctoral graduate student.

No one at the elementary school seemed alarmed by the fact that by third grade, my son, with the above average IQ, couldn’t read and hated himself. I was desperate to get my sweet son back. The little boy who was coming home every day was not the child I had known and raised until public school started. Out of desperation to help my son, I opened the phone book and started calling education lawyers at random. Not one attorney would take my case without several thousand dollars in fees and retainers. I couldn’t get any help, nor would anyone talk to me about the specifics of what was happening to my son because I couldn’t pay for attorney advice.

I finally found a state funded organization that knew all about Special Education rights. I called this organization several times for help and couldn’t get a return phone call. When I arrived at their office, assuming they were open for business, the woman at the desk smirked, sarcastically remarked: “good luck” and with a loud thud, slammed a six inch thick red California Composite of Law book on the desk. Since I had just completed a Bachelors Degree in Criminology, Law and Society at UC Irvine, I figured the red law book was probably exactly what I needed to fight the school.

I spent five weeks, after my son went to bed at night, reading the law book until I passed out from exhaustion. With a little knowledge about special education laws, I began writing letters to members of the school board and the director of education because the laws did not specify how to use the school’s bureaucracy. After my letter writing campaign proved ineffective, I called that state-funded organization back again and begged to speak to someone that could tell me what to do. I was told that the director was too busy to answer individual questions. I found myself stuck alone with a law book and the resolve to continue fighting for my son’s life.

While reading the law in the middle of the night, I found a legal code that required immidiate state intervention, by the California State Department of Education, if a school’s actions interfered with a parent’s ability to work. Because the weekly suspensions, that resumed outside the segregated classroom placement, were impacting my ability to work as graduate student teaching assistant at the university, I was able to get immediate state involvement. Representatives from the California Department of Education, in Sacramento, flew down to Irvine to investigate Turtle Rock Elementary. The investigation happened within one of filing a state compliance complaint against the school district for violating my son’s special education rights to be in school.

In response to my allegations against the school system, all my son’s education records and all the office sign-out sheets vanished. While my state complaint could not be substantiated because the investigators were left with no education records on my child, and no office records showing how often he was sent home, the school was only violated on violating procedural law for not keeping records on a child in special education. Despite the setback, I recognized that loosing all the office sing-in/sign-out sheets (proving how often the principal was sending my son home for bad behavior) was a winning court case for me. I realized that while I did not have records, I had leverage to position my case and win appropriate support without going to court.

Using leverage without an attorney was not easy. The special education administrators in Irvine were bold. The Irvine Special Education Director, the school Principal and the IUSD special education district case administrator brought me into IEP meetings every month. With the silent support of the classroom teacher, these suited bureaucrats lunged at me, sometimes in unison with grimacing faces, to hurl accusations that I caused my son’s problems by demanding mainstream placement and refusing to administer Ritalin. If my love for that boy didn’t outweigh everything else in my life, the intimidation would have been too much and I would have given up the fight.

These meetings were frightening. I was 29 years old, alone, overburdened with first year graduate work and facing a team of unified suited credentialed professionals with power backed a very old and established system they controlled. In fact, during these meetings, suited bureaucrats were lunging at me like striking snakes demanding: “you will agree to no additional services, no behavioral support and special day placement.” Every four weeks I sat through abusive sessions of degradation and coercion only to leave without agreeing to the madness presented by these street-level-bureaucrats. The pathetic education I was pressured to accept stank in its opposition to my son’s needs and rights.

Honestly, I hadn’t yet grasped that I was using law, that I had been taught was for the police to enforce and the courtroom to judge, to make policy for an individual within a public institution. My schedule juggled a full-time doctoral curriculum, graduate teaching assistant job, systematic parenting program at home and special education law study, as well as advocacy, in every 24 hour period. My first grasp of citizen power centered on special education rights giving me veto power in the placement process. As I continued in my study, I realized specific assessments are more necessary than attorneys. I also operated on the premise that these older powerful professionals backed themselves into a corner when they made my son’s records disappear. The meetings got so bad, I began taking a tape recorder to every meeting to have evidence that these professionals were using the IEP process to intimidate and coerce rather than determine evidence based needs. I found the tape recorder eliminated foul abusiveness and seemed to force a level of civility expected in a school setting.

I also learned to connect scientific evidence with the IEP document. I learned to create scientific evidence about childhood behaviors by figuring out that the school had assessments, they never told me about, to explain school based childhood maladaptive behaviors. Therefore, I began submitting written requests for assessments like the Functional Behavioral Analysis. The letter requesting a Functional Behavioral Analysis really unlocked the evidence I needed to get my son appropriate placement and services. Once I got scientific documentation of what was happening in the classroom, the behavior specialist was left without any other options but to recommend a placement in a non-public school setting because my son needed systematic behavior intervention that the public school was not set up to provide for highly intelligent children. It turns out that the law recognizes children need both behavior support and classrooms filled with peers of similar intellectual ability.

Between February and June of 1999, I worked with the State Procedural Safeguards Unit, the laws in that book, the IEP meetings, the tape recorder, and my letters to get my son into a non-public school for average to highly intelligent children with behavioral problems. The public school paid the tuition for my son’s non-public specialized schooling during his 4th, 5th and 6th grades.

I won these changes alone. I never had an attorney nor any council from anyone, other than one life-line at the state Procedural Safeguards Hotline. I was completely denied any information from anyone in the community because I couldn’t pay for that information.

After two years in a non-public school, that did not require children take psychstiumlant or any other type of medication, my happy and healthy son was back and ready to learn to read. The behavioral intervention system at the non-public school helped. My son’s self-image was impacted in a positive way because all the children had similar behavioral problems and intellects.

My son was no longer in an environment organized to praise high achievement and stigmatize low achievement. Behavioral non-compliance, among a population of mostly male students, was the new normal and the behavioral intervention system was applied consistently to all students. This system produced behavioral change and protected the child’s self-image through normalizing behavioral intervention, during critical years in a young boy’s development of self.

The Fight for Literacy

The battle wasn’t over. After years of behavior interference with learning, my son wasn’t reading like other students his age. In fact, reading and writing were huge struggles. By 7th grade, it was apparent that reading and writing instruction wasn’t absorbed during the years of behavior intervention. In mainstream middle school, my son required daily assistance to keep up with modified classwork.

My son was not able to copy daily instructions within the time allotted, nor could he really read everything visually presented in the classroom or in text books. During a middle school IEP, I asked for reading help but was told that my son had summer reading programs to help learn to read and he had resource support to augment the fact that he could not read. I was told the resource class he had was enough to help him keep up in his classes. The district said it is acceptable that a sixth grade student cannot read nor access the curriculum because he could not read. I was also told that my son had to give up all electives in order to have accommodations for his reading disability.

Again, no one in middle school was alarmed by the fact that my son could not read, his IQ was well above average, and his behavior was not a problem. Because I was not a reading expert, I felt like I hit another wall in the school system. I knew my son needed reading intervention but I did not know how to get that help.

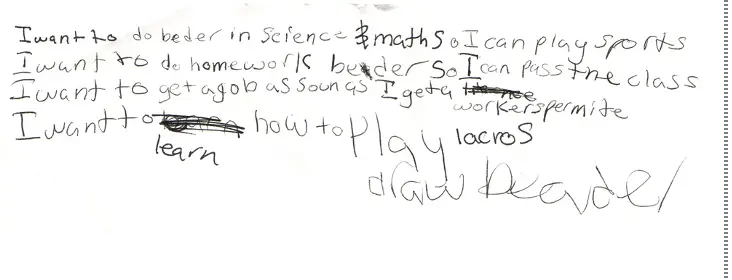

The writing sample, shown in the photo, was my son’s 6th grade high school goals paper. Orally, the boy who wrote the sad paper below could articulate his thoughts, with an educated vocabulary reflecting his home environment surrounded by graduate students. My son’s verbal ability was much high than most youth his age. However, when asked to write, my son’s intellect and articulation diminished greatly. The writing sample motivated me to ramp up my advocacy skills again.

I found a national organization offering parent advocacy training. I privately funded my own special education advocacy training with the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates. In addition, I purchased books on reading disabilities, IQ assessment and reading assessments. I had to understand the relationship between assessment instruments, suspected disabilities, interventions, standardized state testing and work samples. In time, I learned to use the school’s psychoeducational assessments and my son’s work samples to prove the education offered by the school was not appropriate for a child who could not read but has an above average IQ. In other words, I had to learn how to prove my son had a right to learn to read and write. I had to master the practice of using psychological science and the law together.

Reading remediation was hard won. IUSD filed a due process hearing against me because I would not agree to a general summer school program. With the help of our new 2004 ACE team, we were able to settle before the hearing. We proved that my son needed: one-to-one private reading tutoring during the regular summer school weeks at three hours per day, six hours education therapy per week between summer school session and the beginning of the fall semester of his freshman year in high school, and individual remediation three time per weeks, after school, during the school year. These interventions helped. After one summer and two high school years intervention, my son was self-sufficient in school. When my son was caught up in all areas, I moved away from Irvine with my healthy, typically functioning highly intelligent son by my side.

My son experienced a complete transformation after getting the help he needed in school. As a junior in his new school, my son actually said “I love school” and was passing all his classes without extra support. My son discovered he was a very talented pole vaulter. In fact, my son was MVP in Track and Field for Pole Vault his Senior Year of High School, had his personalized letterman’s jacket as a senior and Graduated on time, with his class!

My son’s adult life is good. I consider embracing the challenges, I faced as a mother, character defining moments that gave me purpose and gave my son the life love destined for him. Today, my son has never used drugs and alcohol, has always worked full-time, is married and beginning a family of his own. My son is making it in the USA! I declare profound success and the proven value of parent advocacy in schools!

The fight for my son’s rights consumed my life. As I knit Sociology, Psychology, Law and Bureaucracy into a unified advocacy practice, word spread that I had an ability to help other parents. People in the community began to approach me for help with their child’s IEP problems. As a result, I followed the example of my friend Diana Spatz, of LIFETIME, and started a community based non-profit organization. My mission is to assist parents in securing an appropriate education for their unique children. In 2004, myself, and a friend from graduate school, incorporated Access Center for Education (ACE).

Systematic Lawlessness

My son’s life was saved because of special education advocacy. There is no doubt that the school system is structured to allow academic failure to translate into personal moral and spiritual failure. The lawless treatment myself, my son, and other parents and children experience proves that the school bureaucracy encourages individual leaders to foster the internalization of personal moral failure among children. Meanwhile, credentialed professionals purposely sort failing students into problematic subgroups, often segregated into “special schools” far away from conforming children. This bureaucratic sorting scheme is most visible in high school when policy pushes any child who cannot stay above a GPA threshold into continuation schools mixed with drug and crime entangled students.

Personal responsibility for academic achievement does not apply to the system of lawless bureaucratic sorting I experienced in one of the most wealthy communities on earth. The full effect of school system sorting based on childhood achievement is systematic segregation that funnels boys from classroom failure to adult prisons. My son was systematically made to fail because he was not treated lawfully by any of the school personnel involved in his education between Kindergarten and 3rd grade and between 7th and 8th grade. In turn, my son was personally blamed for that failure. The structure of the school system I experienced was just like every other school system I come up against in California. Within the advocacy community, this system is called the school to prison pipeline.

Across America school systems produce groups of young men who believe they are personal failures, proven by the fact that these men have a life of failure that began in public school. Love and advocacy protected my son from the prison pipeline, created by the public school system. The male prison population represents a majority the adult product of these day-to-day school procedures.

Professional Advocacy

Brenda Received an Echoing Green Foundation Social Entrepreneur Grant to help start Access Center for Education in 2005. Since 2004, ACE has helped approximately 1000 children and trained parents and professionals across the country. Today, ACE is not supported by grant funding and completely reliant upon individual contributions. Please consider helping ACE by donating today!

I have learned that the power to rescue a child’s life is in the hands of parents and advocates. The court room cannot solve the problem of day-to-day procedural non-compliance by credentialed professionals paid to educate children within the public school system. Taking a child’s special education case to due process hearing requires attorneys. Access to attorneys is social class based and parents quickly learn that equality under law means everyone is equally free to hire lawyers. People with money will always be able to purchase access to the justice system. Knowledgeable parents helping other parents is the only way some families can rescue their children from a system designed to create a percentage of failure and future prisoners.

I believe the price I paid to learn how to become an advocate should be used to help others avoid a solo soul crushing costly life consuming battle. Helping others through easy access to advocacy hinders the public school system’s ability to create future prisoners without any accountability. If the prison system has watch dog organizations tasked with holding prisons accountable for lawful treatment of prisoners, why don’t public schools? Aren’t children worth as much as prison inmates?

Witnessing my son’s transformation into darkness and bringing him out of it through special education advocacy revealed my calling in life. The best life I can live is one spent helping other children and parents overcome the pain and suffering of a flawed system that harms children and families. Every child deserves to exit a system of mandatory participation knowing: “I’m okay as a person.”